Callback functions are an essential and often critical concept that developers need to create drivers or custom libraries. A callback function is a reference to executable code that is passed as an argument to other code that allows a lower-level software layer to call a function defined in a higher-level layer(10). A callback allows a driver or library developer to specify a behavior at a lower layer but leave the implementation definition to the application layer.

A callback function at its simplest is just a function pointer that is passed to another function as a parameter. In most instances, a callback will contain three pieces:

• The callback function

• A callback registration

• Callback execution

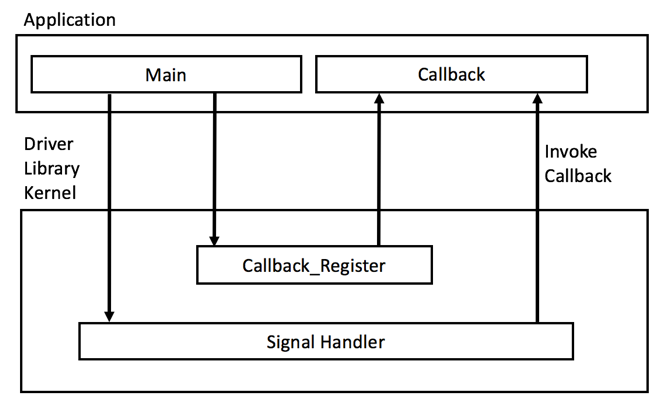

Figure 46 shows how these three pieces work together in a typical callback implementation.

Figure 46 – Callback Example Usage

First, a developer creates the library or module that will have an implementation element that is determined by the application developer. An example might be that a developer creates a GPIO driver that has an interrupt service routine whose code is specified by the application developer. The interrupt could handle a button press or some other functionality. The driver doesn’t care about the functionality but only that at run-time it knows what function should be called when the interrupt fires. The code that will invoke the callback function within the module is often called the signal handler.

Next, there needs to be some way to tell the lower level code what function should be executed. There are many ways that this can be done but for a driver module, a recommended practice is to create a function within the module that is specifically designed to register a function as a callback. Having a separate function to register the callback function makes it very clear to the developer that the callback function is being registered to a specific signal handler. When the register function is called, the desired function that will be called is passed as a parameter into the module and that functions address is stored.

Finally, the application developer writes their application which includes creating the implementation for the callback and initialization code that registers that function with the library or module. When the application is executed, the low-level code has the callback function address stored and when the feature needs to execute, it dereferences the callback function and executes it.

There are two primary examples that a developer can consider for using callbacks. First, in drivers, a developer will not know how any interrupt service routine might need to be used by the end application. If the developer is creating a library for some microcontrollers peripherals, a callback could be used to specify all the interrupts behaviors. Using the callback would allow the developer to make sure that every interrupt had a default service routine in the event that the application developer did not register a custom callback function. When callbacks are used with interrupts, developers need to keep in mind that the best practices for interrupts need to be followed.

Second, callbacks can be used whenever there is common behavior in an application that might have implementation specific behaviors. For example, initializing an array is a very common task that needs to be performed within an application. What if for some applications, a developer wants to initialize array elements to all zero’s where in another application they want the array elements initialized to random numbers? In this case, they could use a callback to initialize the arrays.

Examine Figure 47. The ArrayInit function takes a pointer to an array with elements size and then it also takes a pointer to a function that returns integers. The function at this point is not defined but can be defined by the application code. When ArrayInit is called the developer passes in whatever function they choose to initialize the array elements. A few example functions that could be passed into ArrayInit can be seen in Figure 48 and Figure 49.

void ArrayInit(int * Array, size_t size, int (*Function)(void))

{

for(size_t i = 0; i < size; i++)

{

Array[i] = Function();

}

}

Figure 47 – Function with Callback

int Zeros(void)

{

return 0;

}

Figure 48 – Initialize Elements to 0

int Random(void)

{

return rand();

}

Figure 49 – Initialize Elements to Random Numbers

The functions Zeros or Random are passed into ArrayInit depending on how the application developer wants to initialize the array.

Note: To learn more portable and reusable firmware techniques, check out “Designing Reusable Firmware“